April 24, 2023

In the Spring 2016 issue of The Moving Image, the Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA), author Paul S. Moore, associate professor of communication and culture at Ryerson University in Toronto, Ontario, discusses how ephemera can provide a glimpse of the history of lost silent films in his article, "Ephemera as Medium: The Afterlife of Lost Films". While the word ephemera can be used broadly to encompass objects such as movie posters of all kinds, from lobby cards to half-sheets, one sheets, three sheets, and more, Moore also mentions the growth of digital archives, which offer an even greater variation in film history. For example, lantern slides, which can be easily scanned on a flatbed scanner. Lobby cards, which can be "scanned" using an iPhone. Perhaps even more importantly, the rapid growth of newspaper archives in the United States and other nations.

Because silent film synopses, promotional articles, taglines, and movie posters reveal the history of how silent films were marketed, these materials were made available through the original pressbooks or presskits, many of which are now very rare or non-existent, at least in digital format. Such materials provide the silent film researcher with the ability to see how a particular actor or actress was marketed, learn about the intended audience, and star popularity. It is this type of information which becomes useful in reconstructing a lost silent film, particularly as a preliminary step to the translation of a silent film booklet bearing the title of a lost silent film, published in Spain. It is also helpful to the one conducting the silent film reconstruction to have some background knowledge of the lead actor/actress in the silent film and genre made.

Curiously, Moore does not mention film booklets in his article. In the case of film booklets produced en masse in Spain, there are available titles not only for many silent films, but also early sound films which fall into the category of being lost. Two main sources providing information on the history of these film booklets: Kiosk Literature of Silver Age Spain: Modernity and Mass Culture edited by Jeffrey Zamostny and Susan Larson (Intellect Books, March 15, 2017), and "La Novela Cinematográfica" by Emeterio Díez-Puertas (University of Navarra, 2001), and personal experience with Spanish film booklets will be recounted in this article.

The Early Days of Novelized Film Booklets

Of the many Spanish film booklet titles published between the mid-1910's through the 1950's, two churned out more than just a few hundred silent film titles well into the sound era: La Novela Semanal Cinematográfica published by Francisco-Mario Bistagne, with over 600 film titles, and Biblioteca Films published by Ramón Sala Verdaguer, with over 500 film titles.

La Novela Popular Cinematográfica and La Novela Semanal Cinematográfica, both first published in 1922 are just two of the extant film booklet titles from the 1920's. However, not all of the earliest film booklet formats were devoted exclusively to silent films. Tras la Pantalla published in 1920 was a series devoted to biographies of early silent film stars, as were the series Amor Y Cine published by Villaroel, and La Novela Íntima Cinematográfica (1925).

When were the earliest film booklets published? The late 1910's to early 20's seems to mark the first appearance of these booklets, although prior to that time, theatre novellas were their immediate predecessor. Some of them do not readily exist in digital format for their film titles to be examined and identified, such as Grandes Films Misteriosos, published in 1916 by Gaumont, which remains the oldest film company in operation. A precursor to the standard film booklet of the 1920's, Grandes Films Misteriosos was a pamphlet series, each one dedicated to a particular silent film containing basic information about the film, cast and production crew, often given to a cinema patron along with the price of a ticket. The pamphlet could also be sold individually to an interested person, usually for a few pennies. Comparable to a live theatre program, these film pamphlets established an important place in the manufacture of historical film ephemera. Picking up on these film pamphlets and putting their ideas into motion, Bistagne and Verdaguer created a publishing empire in Spain which retained a steady flow of customers and collectors who saw some personal value in owning a piece of silent film history. Film booklets were sold at kiosks situated outside of cinemas and the near vicinity, in addition to being sold in stationery stores and in the lobby of cinemas. In this way, the cinema patron had the opportunity to own a piece of silent film history in the form of a novelized film booklet while attending the film showing at the same time. Film booklets were also sold through subscription, as a way to interest individuals in collecting and keeping them for multiple readings.

A modern Spanish kiosk. Credit: Guillermo Varela, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Often referred to as "propaganda" in Spain during the time period these film booklets were published, a more modern name would be promotional merchandising, for American silent films that were released on European soil. It should be noted that it was not just American silent films being promoted; silent films produced in Spain, Russia, France, and Germany have also made these booklets, often translated to a Spanish title. For example:

Biblioteca Films #2 No Se Fíe de las Apariencias/Seine Frau, die Unbekannte/His Mysterious Adventure (1923, Germany/Denmark). With Lil Dagover and Willy Fritsch.

Film Booklet Titles

Francisco-Mario Bistagne was in the business of publishing film booklets for over three decades from 1920 to 1950 which culminated in more than 2,500 film titles, both for silent film and synchronized sound film. He is largely credited to what is considered to be the modern film booklet of its time, distributed as a weekly issue. When the first film booklet La Novela Semanal Cinematográfica - also referred to as cinematographic novel - appeared in Spain in November 1922, Bistagne also issued a statement along with his revolutionary new product intended for the masses. Chances are Bistagne and Verdaguer were not aware of the impact their novelized film booklets would have on future generations when many of the silent film nitrate reels would cease to exist, usually through poor storage. These film booklets would remain the only readily available form of documentation for years to come. Perhaps the most telling sentence in Bistagne's statement is the following:

"If our idea is good, we will not have wasted time in vain and our sacrifices will have been few."

This shows that a degree of humility was put into the publication of these film booklets, in addition to a sincere passion for film and giving cinema patrons the opportunity to own what can be considered a keepsake, something that might be passed down to the next family generation. While a parent or might tell their child they saw the silent film "Success" with Mary Astor from 1923 at the cinema, and also own a copy of Biblioteca Films #85 "En Alas de la Gloria", lovingly preserved, the best piece of silent film magic for the child would be to read this particular film booklet, marveling at the reproduced film stills within its pages, reading the story as it unfolds, while sadly knowing at the same time this silent film is lost.

Ramón Sala Verdaguer, Owner of Editorial Alas, published film booklets between 1924 and 1949, churning out over 1,600 film titles. His most popular series were Biblioteca Films (1924-1936) and Films de Amor (1928-1934).

Other popular novelized film booklet titles include: Biblioteca Ilusión, Biblioteca Trebol, La Novela Americana Cinematográfica, Películas Novela Semanal, La Novela Popular Cinematográfica, La Pantalla Literaria, La Novela Gráfica, La Novela Cinematográfica Epoch 1 and 2, Biblioteca Perla, Argumentos de Cine Popular, and Films de Amor.

In addition to these film booklets, a movie card bearing the image of a famous actor or actress was also distributed to the public. Also published under the film booklet title series such as Biblioteca Films and La Novela Popular Cinematográfica, these cards were individually numbered. Highly collectible and tradeable during their time of issue, these movie cards have made their way into many modern silent film collections, including that of the author of this article.

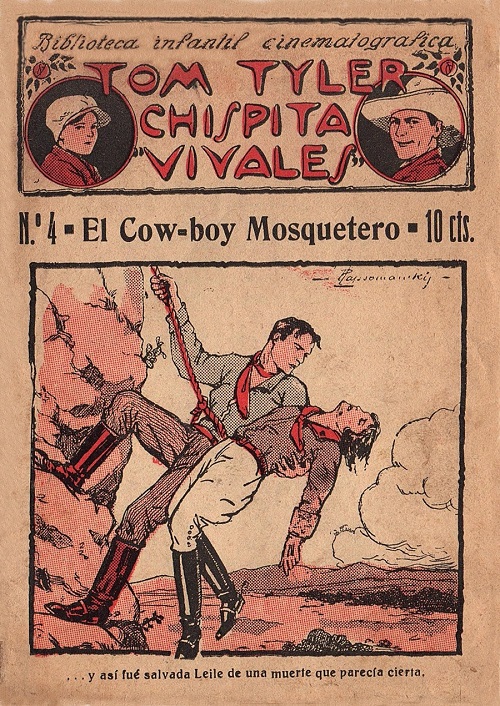

Two film booklet series geared specifically towards children are Biblioteca Infantil Cinematográfica and Cuentos Cinematográficos. It remains uncertain precisely how many issues are in each series, although the former title is mentioned by Díez-Puertas in the table of film booklet titles in his article while the latter, curiously enough, is not. It could be due to the covers of these two film booklets looking similar enough in basic design and font; to complicate matters, Biblioteca Infantil Cinematográfica also issued at least two serials, one each for Tom Mix, one for the French actor Georges Biscot. Another example is "El Cow-boy Mosquetero"/"The Cowboy Musketeer" from 1925 starring Tom Tyler which was published in four issues, with only the first issue bearing a title page and publishing information.

One film booklet series, La Novela Fox, may be of special interest to silent film researchers. Because the majority of silent films that were produced by the Fox Film Corporation prior to 1932 went up in flames on July 9, 1937 when their studio vault storage facility in Little Ferry, New Jersey burned down, all that remains are film stills - and this particular series title. "The Wizard" (1927) starring Edmund Lowe and Leila Hyams was one of those 35mm prints that went up in flames - reputedly the very last print copy - but the first booklet in the La Novela Fox series is "The Wizard"/"El Brujo". More importantly, since the silent film did not adhere so closely to the Gaston Leroux (also the famed author of "The Phantom of the Opera") novel "Balaoo" (1911) that it was supposedly based on, "El Brujo" is worth reading in its surviving film booklet form. Few titles from this series have survived in film archives, while the rest remain unknown with regards to their survival in any film format.

Silent Film Stars and Pulp Fiction

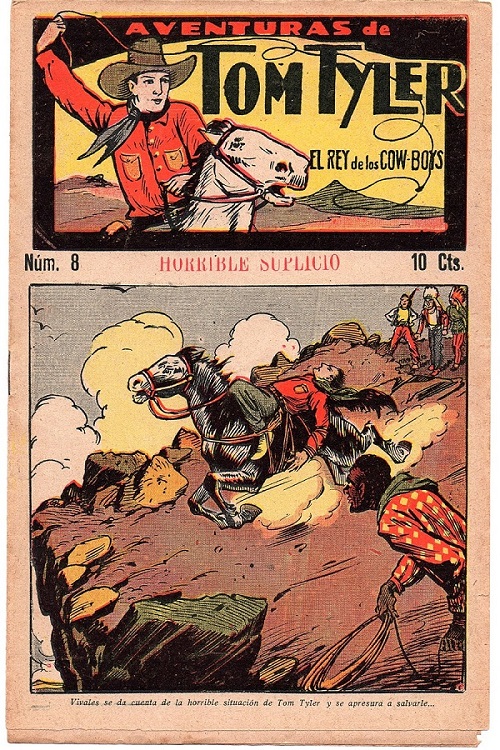

One form of kiosk literature but not a film book per se is a 21-series pulp fiction Aventuras de Tom Tyler: El Rey de los Cowboys published by El Gato Negro, Barcelona in the late 1920's or early 1930's. This publisher also granted Tom Mix with a similar series titled El Cowboy Invencible. Rin Tin Tin, the famous silent film dog, also received own pulp fiction series through El Gato Negro. Mexico's Editorial Novaro publishing company came out with something similar for Buck Jones in the 1960's.

A film booklet series dedicated to western stories was Los Films del Far-West which has 34 issues in its series. Unlike the other film booklet titles mentioned in this section, the Los Films del Far West present something more along the lines of original pulp fiction, with character name changes while maintaining the original film stills within the pages, and sometimes one from a different silent film on the cover.

Creating the Film Booklet

Zamostmy and Larson state the silent film booklets were "authorized Spanish translations of the [film] distributor's original texts and propaganda." In this case, the propaganda would be pressbooks and presskits, while texts could refer to the silent film intertitles, which had to be translated into the nation's language where it would be viewed, along with additional information from the film script. By using intertitles as a means of reproducing the actual dialogue taking place in the silent film, the reader of a silent film booklet can understand what verbally transpired between two or more characters in the film. Editors of these film booklets were often responsible for securing licensing rights to use film stills in the booklets, some of which still exist as actual stills, but many which are long gone in their original 8" x 10" format. The final touch would be the cover, often consisting of a still of the film star, surrounded by a decorative border, while the back cover contained advertising for other issues of the same title series, or more often than not, advertising for a different film booklet title series.

Film Booklets from Other Countries

It may be of interest to note that many of the film booklets published in Spain were also exported to the nations of Latin America, Portugal, even the Philippines, following the Spanish Civil War. Valencian José Bolea Corgonio had a background in law and journalism, which led to the creation of La Semana Cinematographic. Based in Mexico, this title soon joined the popularity of its imports.

Other western European nations came out with film booklets too: The United Kingdom had its popular Boys Cinema which ran from 1919 to 1940, as well as Girls Cinema, published in London by Amalgamated Press. Publication ceased when England entered World War 2 in 1940 due to paper rationing. By the late 1940's, publishing resumed in the form of Annuals, hardbacked series of the weekly Boys Cinema throughout the year. France had its Le Film Complet and Les Films du Far-West. Les Films du Far-West runs on a similar theme with Spain's Los Films del Far-West with a few differences: publishers, location, and appeal to audiences who favor westerns at their local movie house. Les Films du Far-West has a total of 158 issues in the series and was published from 1930 to 1933 by Les Editions Modernes. Given France's attitude towards filmmaking, not to mention the nation's contributions of filmmaking inventions from cameras to, it can come across as a big surprise that an interest in silent films of the western genre take hold in a culture that treats filmmaking as an art form.

Identifying Film Booklet American Titles

A sometime challenge is the identifying of Spanish film booklets with their English titles as the silent film was released under. The misspelling of an actor's name on the cover of the film booklet can also be an issue; for example, the cover may bear the star's name of Edward Carle, which in reality should be Eddie Earl. Then there is the issue of silent film character names being modified from the English in the novelization of the silent film, possibly to avoid a misinterpretation in Spanish. Because these silent film booklets contain numerous film stills in them, some of which have been lost to the mists of time, can also be used to help identify rediscovered silent films.

The Future of Spanish Silent Film Booklets

According to Zamostny and Larson, the primary reason for the mass publication of kiosk literature, including silent film novelizations in the form of booklets, was to increase literacy among Spain's population. However, a better reason for the existence of these film booklets is that Spain could publish them and could afford to publish them, up until Spain's Civil War (1936-39). The growing demand for American silent films, especially Spain's attitude towards the standard western film, which remains the oldest continuing genre of film ever made in the United States, combined with aggressive marketing of these silent films, and the spawning of consumer movie magazines like La Pantalla and El Cuento Semanal which soon gained a wide readership, especially among women. Novelized film booklets of these American silent films were obviously saved, collected, and properly stored, many of which have survived today.

Taking into account the pre-existence of the silent films in their original 35mm, five reels or more, the efficient production methods that went into these film booklets, along with the fact that 70% of all feature length silent films produced before 1929 are lost, one might be astounded to learn that quite a few of these booklets are the only surviving remains of lost silent films.

As the owner of a small collection of these film booklets - a number of them for lost silent films (the first one I ever purchased was Biblioteca Films, "El Valiente de la Pradera"/"Lightning Lariats" (1927) back in August 2016) - proved to be more than just a way of getting in touch with silent film history; I recognized that this was in fact a record of a silent film long considered lost to time. Even though a complete 35mm print of "Lightning Lariats" eventually surfaced at the Gosfilmofond film archive in Moscow only a few years later, the possibilities of the small 4 1/4" x 6" booklet of fragile paper, red leaf design with the title Biblioteca Films in front of a movie camera illustration - and an attractive oval-shaped still of the silent film star on the cover became obvious to me. It was not long before I found myself traversing the world of these film publications, the many different series titles, and publisher names of which remain little known in the United States but remain part of Spain's film culture heritage. Being able to own a number of these film booklets allowed me to complete three lost silent film reconstructions to date, with the possibility of more being done.

For the novice of silent film history and Spanish film booklets, there remains much more than a visual pleasure to see a single issue for a long-lost silent film: it is the key to bringing that lost film alive into the present.

Copyright 2014-2025 Monographs of Reality. No part of this website or its articles may be reproduced in any format.